As the human-computer interaction field keeps growing, it has already shown how human psychology can deeply influence user experience. Taking the opposite perspective, Clifford Nass, a communication researcher, has dedicated his last researches to the feelings that users attribute to computers.

Among 4 specific experiments, he wondered how users react to a computer that behaves like a human. Here’s which human traits he found have a greater impact on users.

Users’ like computer praises and compliments

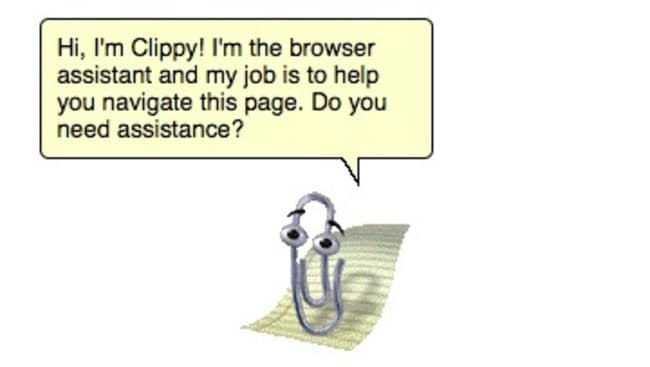

Among all human-machine interaction case studies, Clifford Nass was greatly inspired by the Clippy avatar that helped Microsoft Word users in their tasks.

Intrigued by the extremely negative reputation the tool has garnered against it, he and his team conceived an experiment that sought to reverse their attitude of distrust towards it. They made Clippy asks users for feedback, allowing them to express their frustration.

Where this technique was very powerful is that it made Clippy say that he was going to complain to the Microsoft Teams on their behalf. By putting himself on the user’s side, users greatly increased their appreciation for him.

Following the results of this experiment, Nass and his team tried then to investigate the impact that computer comments about users can have directly. They conducted experiments attempting to analyze the reaction of users to praise and flattery.

For example, they asked two groups of participants 12 same questions. Both groups worked on a computer that was programmed to give them flattering comments at specific times. However, the first group was told that the comments were meaningless, and the second that they were related to their performance. As it turned out, both groups appreciated the computer’s praise just as much, although the first group knew that the comments had nothing to do with it. Users are therefore by nature sensitive to positive statements.

But not all types of flattery work the same way. In another experiment, the researchers had the participants drive in a car that gave them comments to encourage them on their journey. The first group received messages throughout the trip insisting that they seemed good at driving, and that it had to be very easy for them. The second group was hearing messages highlighting the difficulties they were facing, and pushing them to do their best.

While both groups did the same course, the second group did well and appreciated more the computer’s feedback. The first group, on the other hand, found the voice superficial and annoying, and even decided to fool the system by driving erratically.

All these experiments show the power of balanced flattery on the user.

Machine personality and similarity attraction

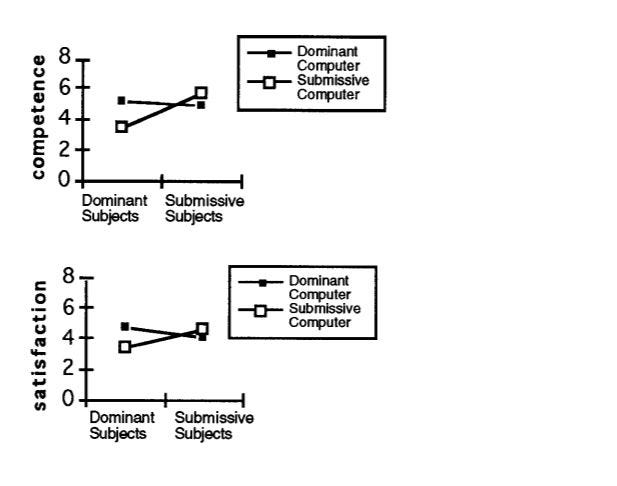

Nass and his team also studied the impact of the different personalities that computers can display. Whether dominant, friendly, cold or submissive, users always assimilate machines to personality traits.

In particular, the researchers noticed how a similar psychological profile made machines more attractive to users. To test their hypothesis, they designed a synthetic voice software that helped two groups buy a book. The first group defined themselves as extroverted and heard a voice that had extrovert overtones (more direct and assertive). The second group turned out as introvert and faced a voice that sounded more introverted (more hesitant and questioning). It turned out that participants identified more easily with a voice that matched their own, and were more convinced to buy the book.

But if users appreciate a service with personality traits similar to their own, they might also appreciate a behavior that gradually adapts to their own. Nass and his team had individuals play a survival game in collaboration with a computer. They had to agree on a list of items to take to survive on a remote island.

At the beginning, they made the computer speak in a way that made it behave with opposite traits (more introverted and submissive with an extroverted user and vice versa). Then, they varied the message sent by progressively changing the tone to match their personality (in this case, messages that were more and more assertive and sure of themselves). Far from putting off users, they appreciated the machine even more in that it unconsciously adapted to their attitude.

We see here the importance to add a strong and adaptable personality to machines interacting with users.

The importance of psychological identification

As users collaborate more and more with computers in the workplace, another interesting question is how humans and machines can function as a team.

The idea of the Stanford researchers was to have two teams of individuals compete with their computers. Both groups wore a blue wristband, identifying themselves as the blue team. But while the first group worked with a computer that also had a blue indication, the second group had a computer that displayed “Green computer”. The users played with these computers to solve the Desert Survival Situation problem already mentioned above. While the goal was for users to get along with the computers, they were programmed to diverge in their choices.

At the end of the study, it was found that participants were more likely to work with their computer when it was visually the same color as them and more likely when it was a different color. This shows the power of visual identification with a common group in human-computer interaction.

Matching User’s emotional valence

This collaboration can be further strengthened through shared emotions. Although machines do not naturally express emotions, they can convey signals and messages that can influence the emotion of users.

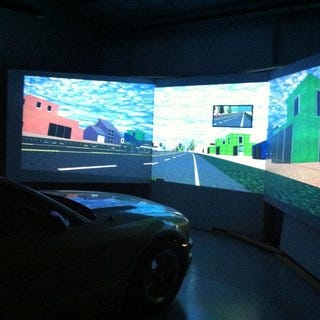

Nass and one of his students tried to assess the emotional effect of machine speech during a well-framed driving simulation. They put participants in driving simulators, with a robot passenger giving feedback during the ride. Before starting, they were subjected to videos that either put them in an angry or melancholy position. In the next experiment, the participants deliberately faced obstacles of varying magnitude that increased their frustration. The robot meanwhile commented each moment of frustration by reassuring differently according to the group.

However, for the more angry people of the group 1, it sympathized with the drivers’ frustration and blamed the bystanders and other drivers in the program. Whereas for the saddest Group 2 participants, it recognized the overall difficulty, and empathized with the driver. Depending on the emotional content of the participants, the results were thus differentiated.

The result was that the robot did indeed manage to empathize with them by adopting their speech: angry users were more reassured by a machine that bore the blame with them, and sad and disappointed ones by recognizing the magnitude of the effort required. So designers could benefit from computer that adapt its tone and words to the emotional mood of the user.

As you can see here, computers have the ability to feel like human to the users and nurture an emotional relationship with him. But designers need to leverage various psychological mechanisms to create a complicity with them!